May 08, 2025: Full Remarks

Good afternoon everyone, and thank you for the opportunity to join this vital discussion.

Let me begin by expressing my gratitude to the Department of History and Archaeology at the University of Nairobi for organizing this important seminar, and to Professor Michael Chege for his deeply reflective presentation. I am equally honored to share this panel with Wambui Wamai Jacqueline, whose work on labor justice across Sub-Saharan Africa continues to inspire new forms of worker resistance and solidarity.

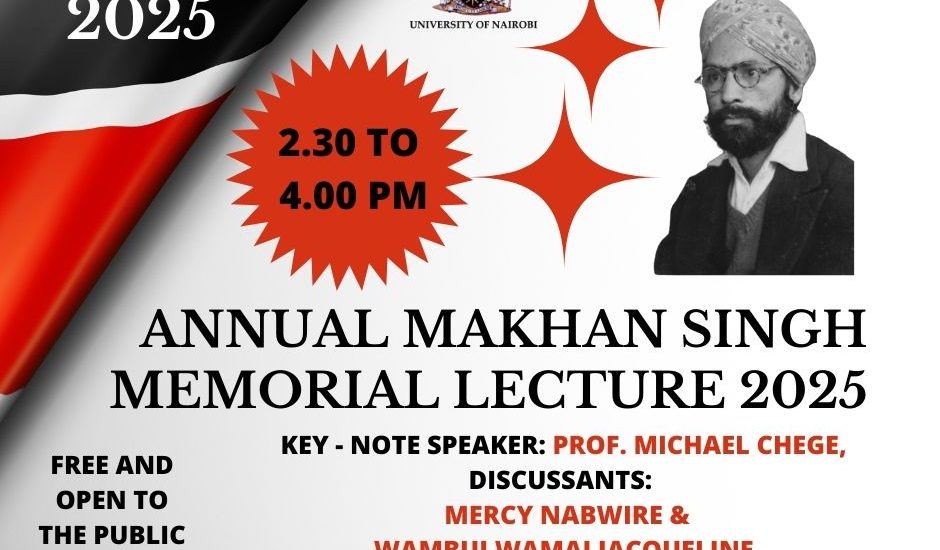

Today’s lecture holds special significance: it is dedicated to Zarina Patel, the daughter of Makhan Singh, a courageous activist, editor, and author, who has preserved and championed her father’s radical legacy against forces of erasure and historical amnesia.

As we honor Zarina Patel, we must also recognize that the struggle for labor rights is inseparable from the struggle for gender justice. Women workers have long been at the heart of Kenya’s labor force, from domestic workers to agricultural laborers, to nurses and educators, yet they remain among the most exploited, the least protected, and the most invisible. Organizing women workers is not simply a moral imperative, it is a strategic necessity if we are serious about building a labour movement that reflects and represents the realities of the Kenyan working class today.

Today, we reflect on the life and struggles of Makhan Singh, a visionary who recognized that workers’ liberation and national liberation were not parallel struggles, but one and the same. In remembering Makhan Singh, we are not merely paying tribute to the past; we are confronting the unfinished business of worker emancipation in Kenya and around the world.

As the current National Treasurer of the Kenya Medical Practitioners, Pharmacists and Dentists Union (KMPDU), I speak from the frontlines of a healthcare system in crisis, and from within a labour movement under siege. The struggles Makhan Singh faced remain strikingly familiar: the continued erosion of workers’ rights and protections, suppression of union activity and co-optation of union leadership, the creeping yet brazen privatization of essential public services like healthcare.

But we must be clear: today’s oppression of workers is not confined within national borders.

Kenyan workers, like millions around the globe, are trapped in a global economic architecture designed to extract labour while erasing rights. Through transnational supply chains, deregulation, and financialization, globalization has decimated workers’ bargaining power, entrenching precariousness particularly in the global south. Neoliberal globalization has not brought prosperity to the majority; it has entrenched precariousness, particularly in countries like ours. It has created a hierarchy of labor , stratified by geography, race, gender, and citizenship, with African workers too often relegated to the most disposable positions in the global order.

And yet, we must also confront our domestic truths. In Kenya, only about 20% of workers are employed in what we define as the “formal” sector. The remaining 80% labor in what is euphemistically referred to as the “informal economy” or “jua kali”. They include domestic workers, casual laborers, mama mbogas , boda boda riders, artisans, and many others.

Is “informality” a neutral term, or a political tool that excludes workers from social protections, collective bargaining rights, and even recognition as full participants in the economy? These categorizations of formal and informal are not neutral. They are ideological categories that obscure the realities of exploitation and justify exclusion from labor protections, social security, and political voice. They only serve to marginalize and invisibilize the majority of Kenyan workers, denying them protections, representation, and dignity.

We must then ask: Whose interests are served by categorizing the majority of Kenyan labor as “informal”?

Now is the time to rethink our definitions, to redefine what constitutes “work,” “worker,” and “workplace” in the Kenyan context. We must reclaim the category of “worker” from these technocratic boundaries, for all who labor, and not only those recognized by outdated colonial and neoliberal frameworks. If we fail to do so, we risk building a labour movement that only speaks to a privileged minority while abandoning the majority to precarious survival, outside both legal and political frameworks. We must begin to build a labor movement that centers the majority, not one that champions the interests of a shrinking, privileged few.

This is where the concept of social movement unionism becomes critical. Social movement unionism is not optional, it is essential. We can no longer afford narrow, wage-based unionism that ignores the political economy in which workers live. We must embrace unionism that fights for housing, education, healthcare, dignity, environmental justice and political participation. A movement that connects across sectors, regions, and struggles.

The future of labor organizing in Kenya and globally lies in building solidarities that are intersectional and international. Even though our struggles may appear different, our enemies are increasingly the same: austerity, privatization, militarized capitalism, and a ruling class committed to profit over people. This is why we must forge transnational solidarity among African workers, with diasporic communities, with migrants and refugees, and with public sector workers in the global north who are also facing the devastating consequences of neoliberal policies.

At the same time, we must not be afraid to call into question the ideological orientation of Kenya’s labour movement leadership and especially our largest workers’ federation, COTU- Kenya (Central Organization of Trade Unions- Kenya). A labour federation must be the conscience of the working class, not an appendage of the political elite. If COTU fails to challenge neoliberal policies, privatization, casualization, and the exploitation of women and informal workers, then it must be called to account. The Kenyan labor movement deserves leadership that is radical, independent, and accountable to workers and not to politicians or capital.

All this cannot be achieved without a robust intellectual infrastructure. This is where the academy must also step forward. We need rigorous academic engagement with labour; critical scholarship that engages directly with labor struggles, not as a technical or historical topic, but as a living, breathing site of political struggle. We need class analysis, political economy, labor history and feminist theory at the center of curricula. Without a rigorous, politically conscious intellectual foundation, our movements will remain fragmented and reactive, rather than visionary and strategic.

Makhan Singh understood this. He knew that ideas mattered as much as marches. He was not just an organizer; he was a thinker, a journalist, and a political educator. He knew that movements are built on consciousness, and not just anger. The future of the labour movement in Kenya will not be decided by policymakers or capital alone. It will be shaped by the consciousness, organization, and determination of workers themselves, formal and informal, local and global, historic and emerging. Our task is to make that future possible.

Today, I call on all of us:

- To honour Makhan Singh and Zarina Patel not by nostalgia, but by action.

- To organize across formal and informal divides, across gendered inequalities, and across national borders.

- To reclaim labor as a political project, not just an economic negotiation.

- To build worker-centered solidarities that transcend the artificial hierarchies imposed by globalization.

Because the future will not be given to us. It must be organized by us, for us, and with us.

Thank you.